Fat Facts: How Excess Fat Storage Can Grow A Deadly Organ

Adipose tissue, or body fat, can be stored either subcutaneously (under the skin) or viscerally (surrounding the internal organs). The location on the body where fat is stored varies depending on gender, race, and genetics. For instance, during times of weight gain, women tend to store fat around the hips and thighs, while men deposit around the middle. Thus, the broad generalization is that women resemble “pear” and men resemble “apples” Besides the external/cosmetic result, the internal/clinical ramifications of fat storage depend on the location as well.

Adipocytes, or fat cells, make up adipose tissue and play a critical role in energy regulation and homeostasis. During infancy, adipocytes are brown in color and function completely opposite to the white adipocytes found in adults. Brown adipose tissue utilizes energy to mitochondrial uncoupling proteins that convert the brown adipocytes into the white adipocytes, which function as energy storage facilities.

As energy intake exceeds energy consumption, these white adipocytes will store this extra energy as triglycerides. During starvation, the body depends on the adipocytes to release excess energy stores in the form of free fatty acids. However, if the body is in a constant state of excess energy, the adipocytes steadily enlarge. Once an adipocyte reaches its maximum capacity, the cell divides (also known as hyperplasia) leaving the body with additional repositories for energy reserves.

The body’s ability to create new adipocytes all but diminishes after puberty. Only in extreme cases does adipocyte hyperplasia occur in adulthood. This shows how being overweight as a child can lay the foundation for a lifetime of obesity. Weight gain as an adult is mainly achieved through adipocyte enlargement or hypertrophy. This simple action seems to be the key contributor to the varying and catastrophic effects of obesity.

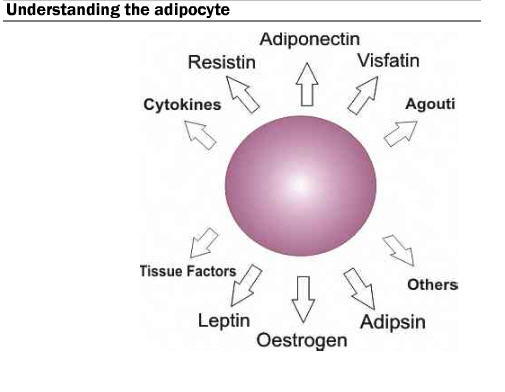

During hypertrophy, the adipocyte secretes various molecules known as adipokines. These adipokines act as signaling messengers and are believed to be involved in some of the harmful side effects and co-morbidities associated with obesity. The key concept is that adipose tissue is a highly active metabolic and endocrine organ and can lead to serious consequences if increased significantly by weight and by size.

Increased weight gain makes it more difficult to feel full. Leptin is one of the hormones secreted, and it acts as a circulating signal to reduce appetite. Obese individuals are subject to high concentrations of leptin, which can develop into a resistance to the hormone in the muscle, liver, and hunger-related neurological pathways. Due to the leptin signal resistance, obese individuals have difficulty feeling satiated during or after a meal.

Data suggest that adipocyte secretions are involved in metabolism and the onset of type 2 diabetes. Though there are conflicting results, numerous studies suggest there is an increased resistin concentration in the body as a result of increased adiposity. Researchers suggest that the higher resistin concentration is correlated to insulin resistance. Additionally, as fat mass increases, TNF (tumor necrosis factor)-alpha increases. TNF-alpha negatively impacts blood sugar absorption by the liver and muscle and signifies another potential cause of insulin resistance.

Excess is always a concern, and more fat can lead to heart disease and even cancer. In obese individuals, adipocytes are more regularly releasing energy in the form of triglycerides. Elevated levels of triglycerides are linked to atherosclerosis and thus believed to increase the risk of heart disease and stroke. Adipose tissue also releases oestrogen, which when unchecked by the necessary countering hormones (progestin or estradiol) can increase the risk of cancer.